A marvelous mosaic mystery: the Cote d’Azur in the 1950s, an enchanting young lover, and the missing mosaics of Pablo Picasso. An intriguing story about how one of the 20th century’s most influential artists explored the mosaic medium, and ponder what’s happened to the works since?

Where’s Pablo? The Mid-Century Mosaics of Picasso

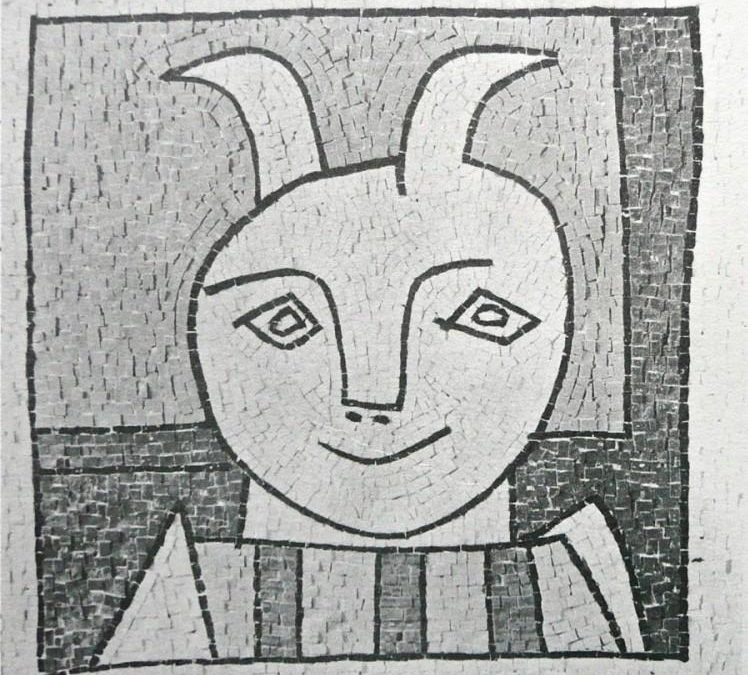

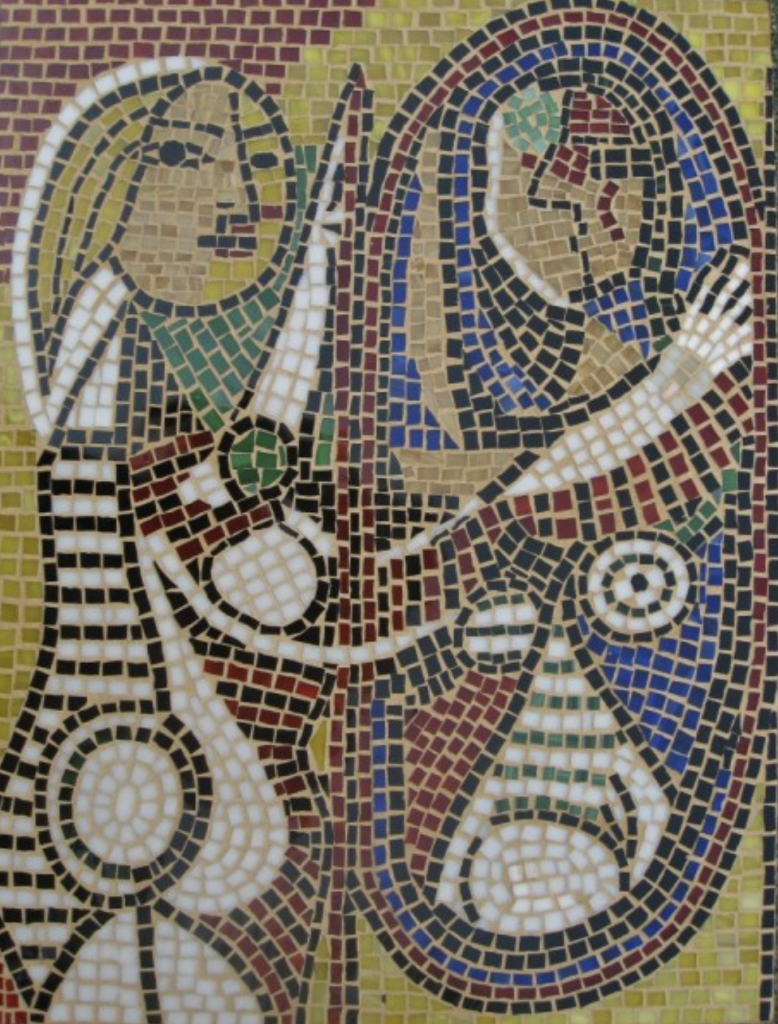

Pablo Picasso “Tête Fauve” (Faun Head) Executed by Hjalmar Boyensen, circa 1957-58

By Lillian Sizemore

Originally published on Mosaic Art NOW, May 31, 2012. UPDATED here on Nov. 25, 2023.

While reading a 1963 copy of Mosaics: Design, Construction and Assembly by British mosaicist, Robert Williamson, I discovered Pablo Picasso’s mid-century mosaics. Williamson published several pages of these works, some of which are reproduced in this article. Picasso (1881-1973) is renowned for his extraordinary artistic experiments in painting, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, collage and even stage design; but I’d never heard Picasso’s name associated with mosaics. I’m excited to report he did not leave this stone unturned, collaborating with mosaicist Hjalmar Boyesen, who executed Picasso’s designs.

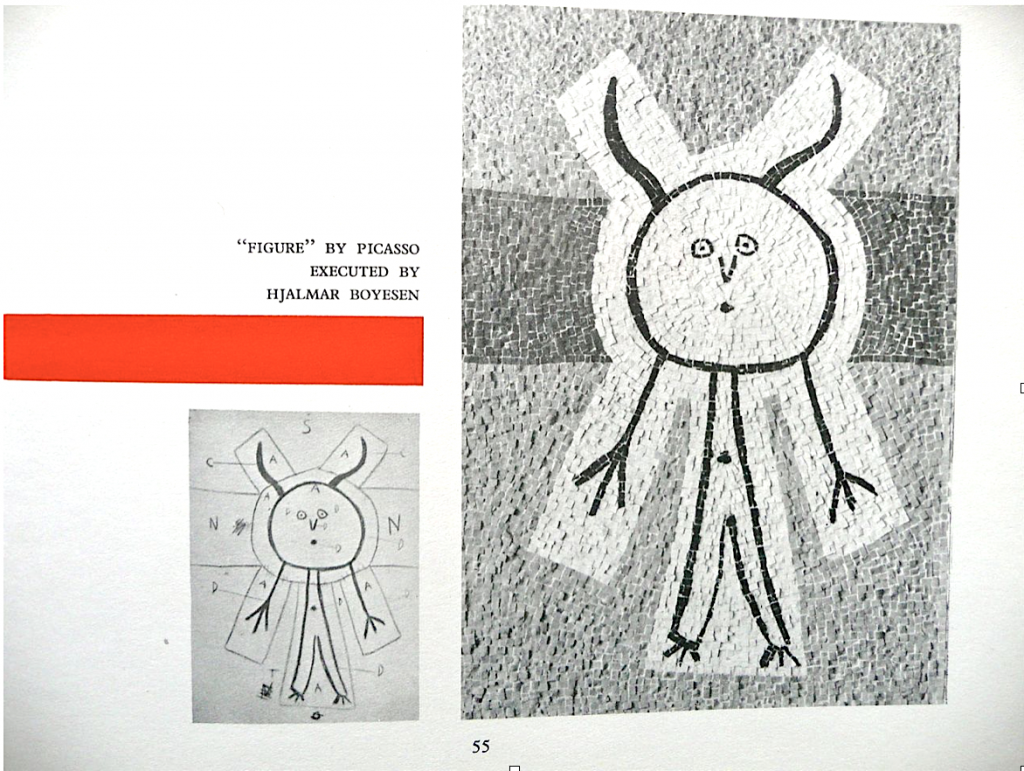

A sample page from British mosaicist Robert Williamson’s 1963 book. At left, Picasso’s sketch showing color choices; at right, Boyesen’s finished work. The mosaics published in this chapter would have been “of the moment” having been made sometime between 1955 – 1959. This would indicate that Boyesen and Williamson were contemporary colleagues, both working in mosaic during these years.

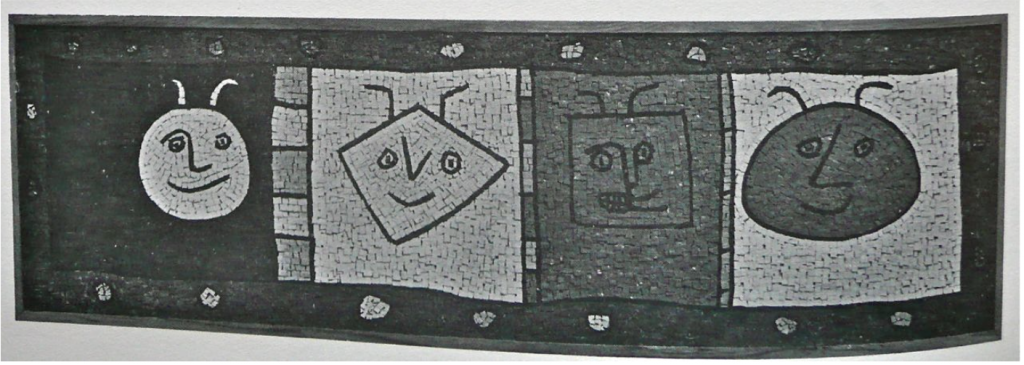

According to a Dorset (UK) newspaper article, artist Hjalmar Boyesen and Picasso became acquainted when Boyesen served as an American soldier during the liberation of Paris in August, 1944. Picasso’s first major mosaic work was the 1.5 ft. x 4 ft. plaque shown below. Though the photo was in black and white, Williamson’s accompanying description states, ”it has been done in six shades of grey, one large area of white, and several smaller areas of color.” To my observation, the inspiration for this design references a filmstrip or photographer’s contact sheet. The Cannes Film Festival, the many celebrities who visited Picasso’s Cannes studio, and Picasso’s own cause célèbre were undoubtedly influencing his work.

Quatre têtes de faune, 1957, Image from Williamson’s book, attributed as Picasso’s first design for a mosaic, executed by Hjalmar Boyesen.

[UPDATE: “Quatre têtes de faune” was located in a private collection as a result of publishing my original article in 2012. In May 2023, Christie’s auction house listed the work echoing observations from this article: “The composition’s vignette-like structure, resembling a film strip, is fitting in the context of Cannes and its festival, which Picasso attended over the years. Furthermore, translated into this medium, the faune, a recurring motif in Picasso’s oeuvre, takes on a new twist – its playfulness accentuated, and Mediterranean origins recalled.”]

Attributed as Picasso’s first design for a mosaic executed by Hjalmar Boyesen.

UPDATE: as a result of the original post, I was contacted and located this mosaic in a private collection. Sold at auction in May 2023, image courtesy Christies. PABLO PICASSO (1881-1973) AND HJALMAR BOYESEN (1920-1958)

“Quatre têtes de faune”

signed and dated ‘Picasso Janvier 57.’ (on the reverse)

mosaic on board, 18 1/8 x 60 1/4 in. (46 x 153 cm.)

Executed in January 1957; unique.

Cote d’Azur in the 1950s

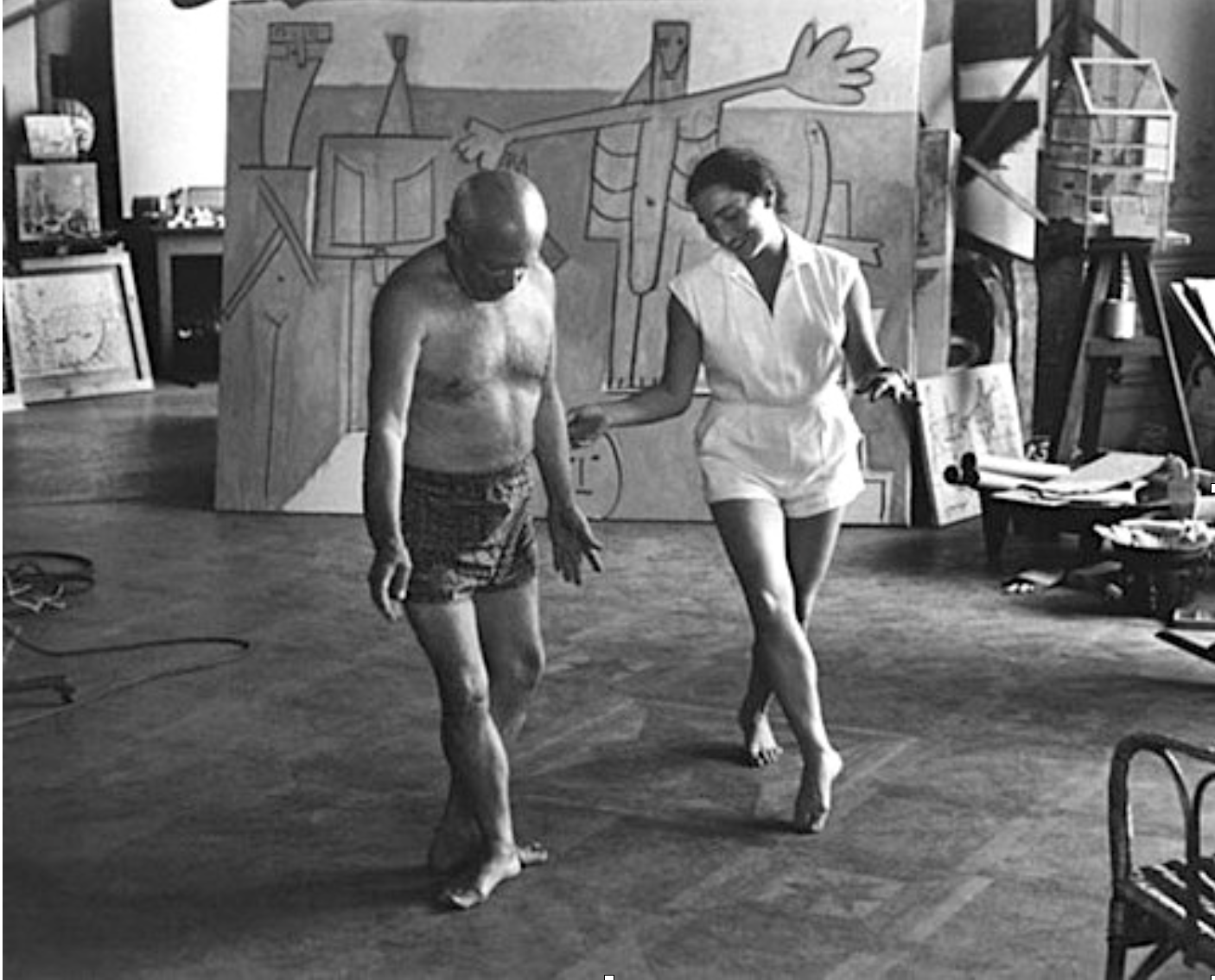

The decade after the World War II was a very prolific time for Picasso. It was in the Cote d’Azur he began drawing on the Mediterranean sources that had inspired him in earlier years. The warm, sunlit coast and a return to family life renewed Picasso’s inspiration after the devastation of the war years. In the mid-50s, Picasso was living in the villa La Galloise, located in the village of Vallauris, outside of Cannes in the south of France. From 1943 to 1953 he lived with painter, Françoise Gilot, (b. 1921 – UPDATE: d. June 2023) with whom he had two children, Claude born in 1947 and Paloma in 1949. They never married because Picasso’s former wife would not grant a divorce. Yet by 1953, Gilot had had enough of Picasso’s infidelities, and left Picasso taking the children with her. He was angry—Gilot was his first (and only) partner to leave him. Not to be undone, Picasso had set his eye on yet another young lover…

Picasso and Jacqueline Roque frolic in the villa “La Californie” in Cannes, 1957, © David Douglas Duncan.

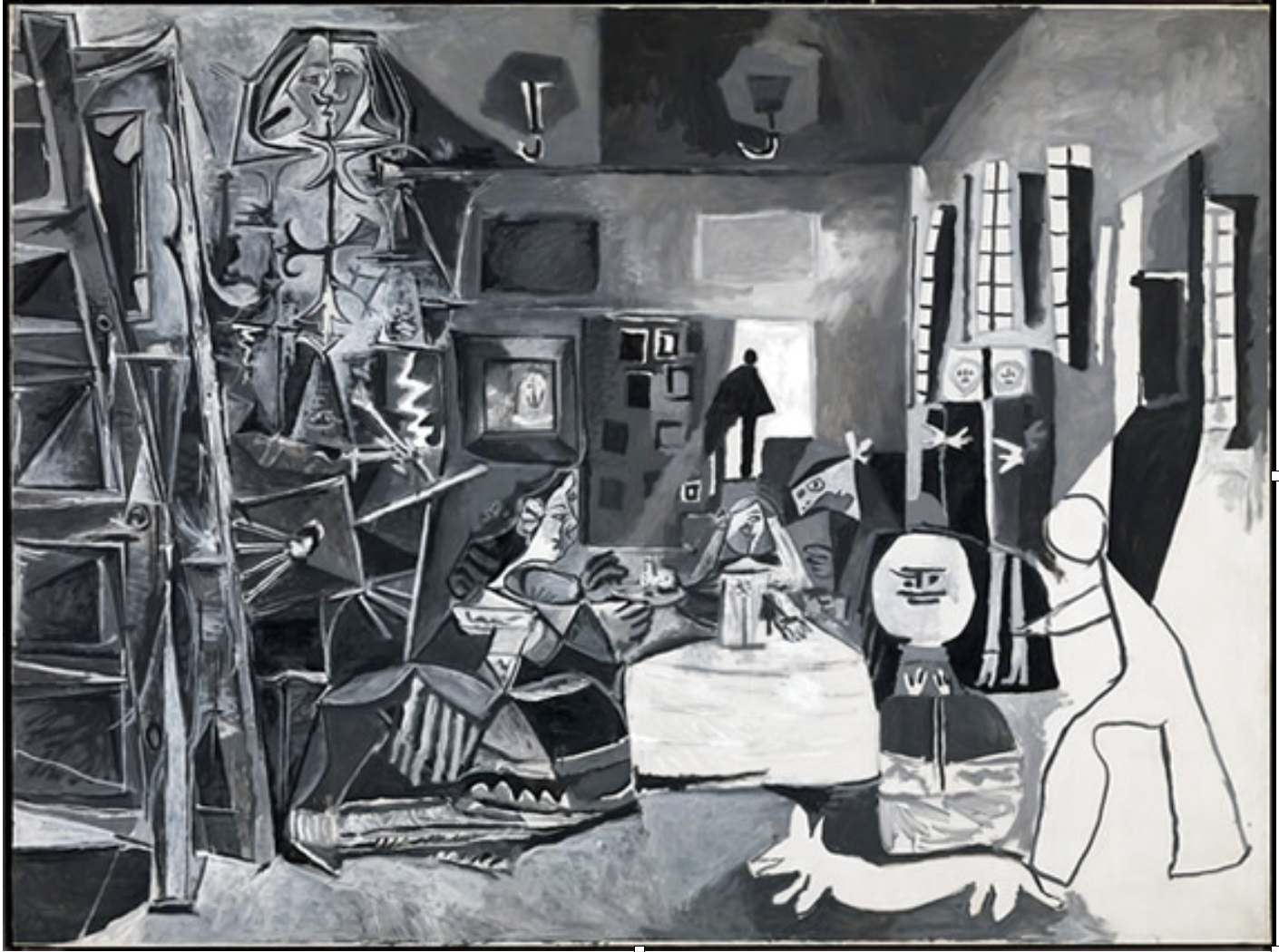

Picasso was relentless in his serial pursuit of women decades younger than himself. Picasso met Gilot when she was 21 and he was 61. Once Gilot left Picasso, his new muse and lover became Jacqueline Roque, (1927–1986), a beautiful and vivacious ingénue, 46 years his junior. Jacqueline worked at the local Madoura Pottery where Picasso was furiously making ceramics by the thousands. Even at age 76, Picasso still possessed an unceasing capacity for making art. Besides his ceramic editions, Picasso was creating a series of over 50 versions of Velasquez’s Las Meninas, a painting depicting the Spanish court of Philip IV of Spain in 1656. The mosaics date from this same intensely active period.

“Meninas after Velasquez”, 1957, Oil on canvas, 194 x 260 cm, Museu Picasso de Barcelona/Succession Picasso/DACS 2009.

Diego Velázquez, “Las Meninas” 1656, Oil on canvas, 318 x 276 cm. Photograph: Bridgeman Art Library

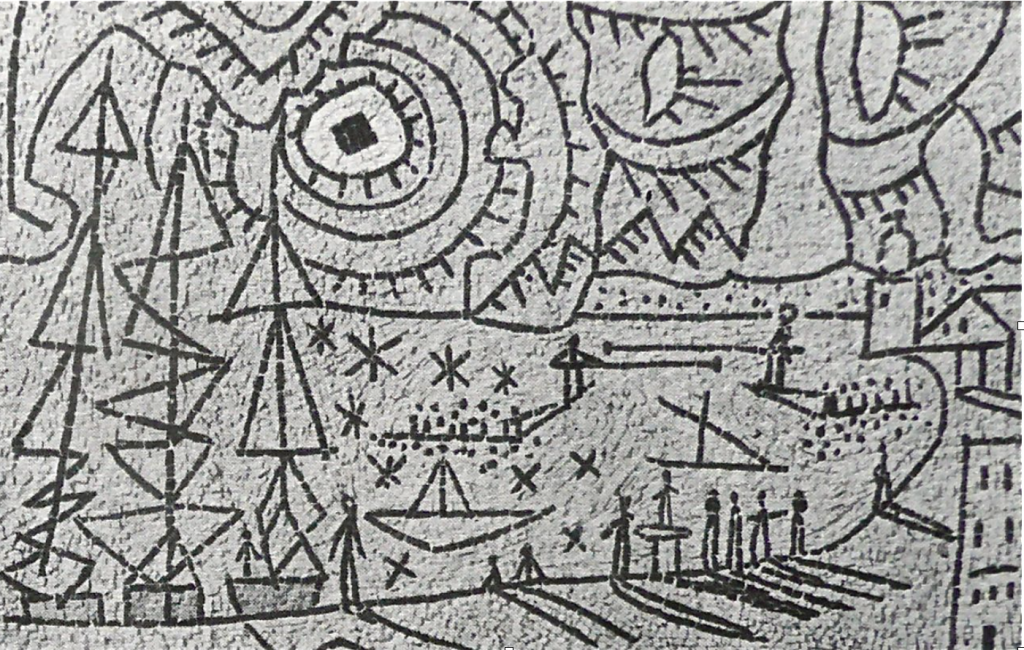

By the summer of 1957, Picasso began making sketches specifically for mosaics, working closely with Hjalmar Boyesen in the mosaicist’s Cannes studio. Boyesen was a mosaicist with a penchant for abstraction. At the time of this writing, it’s unknown how he came to work with Picasso in southern France. There was a vibrant artistic community in Cannes, and their friendship was already established from Paris. Was it perhaps Boyesen who suggested the medium to Picasso? Did Picasso see Boyesen’s work and decide he wanted to work in the medium as well? Did Picasso invite Boyesen to Cannes? [UPDATE: we discover in a letter of agreement (dated 26 February 1957) that their collaboration started at the beginning of 1957 and that Picasso’s gallerist, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979) played a role. In this letter Boyesen makes a legal agreement to not make any copies of the mosaics by himself, and that he would be paid upon completion of each finished work. From this letter, I suggest that the inclusion of mosaic to Picasso’s oeuvre may have been a business move instigated by Kahnweiler himself, for the Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris. Mosaic expanded Picasso’s popular decorative art offerings, beyond ceramics. One cannot consider the mosaics of Picasso without also examining the concurrent works of Fernand Léger, Sonia Delaunay, Marc Chagall, Gino Severini, Jeanne Reynal, and others, who were successfully experimenting with and selling mosaics, provoking a rise in popularity amongst modern artists in the mid-20th century. Picasso’s meeting with mosaicist Boyesen in Cannes would have presented the right moment to introduce new work.]

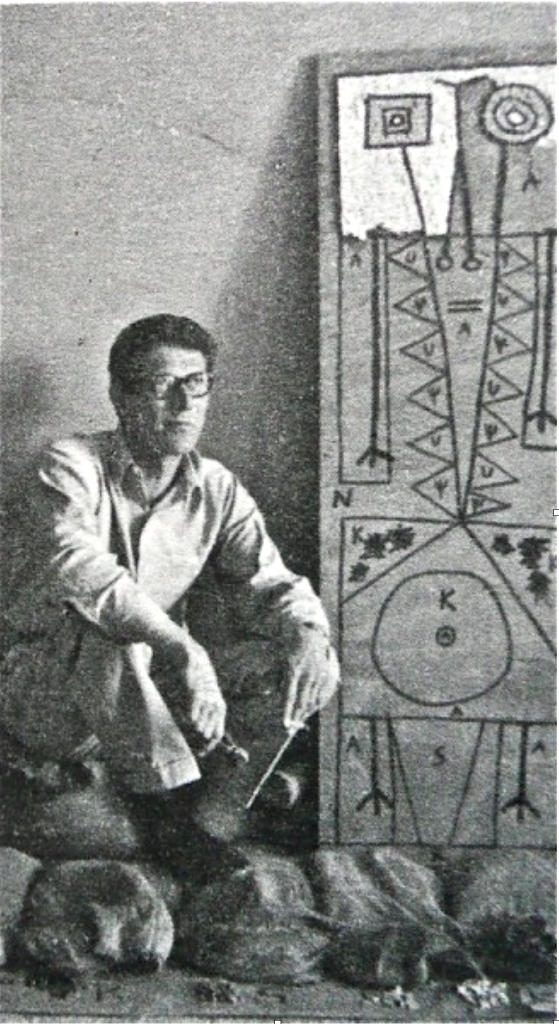

Mosaicist Hjalmar Boyesen in his Cannes studio kneels in front of a Picasso panel-in- progress with bags of stone and smalti (glass) at his feet. Color choices are indicated with letters in the segmented design, circa 1957.

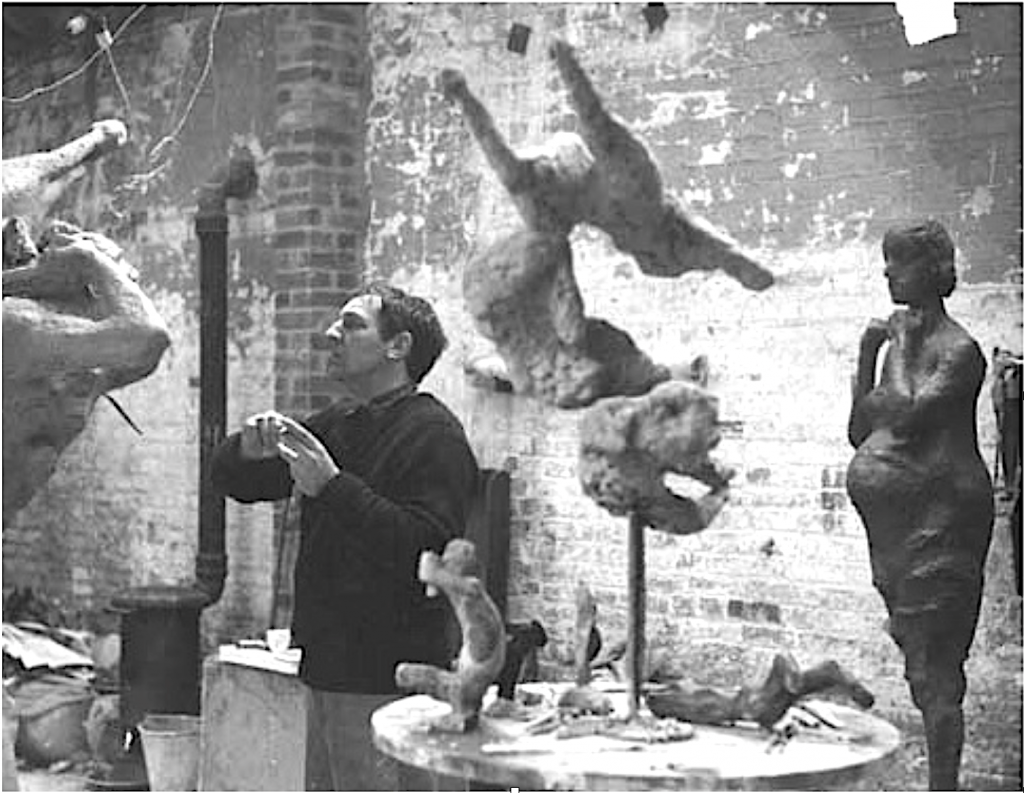

Picasso’s mosaic panels were executed by Boyesen, assisted by an emerging British sculptor, Ralph Brown, who was on a study sabbatical in Italy that year and came to Cannes to work in Boyesen’s atelier. That summer in Cannes, the young sculptor was making his way around the Italian and Paris art scene, meeting Giacometti and many Italian sculptors of the day. The famous sculptor Henry Moore collected some of Brown’s early works and helped to launch his life long art career. Ralph Brown went on to teach at the Royal College of Art and maintained a life long sculpting career.

Sculptor Ralph Brown, shown here working in his Digwell Studio, UK. Brown assisted Boyesen, and found much inspiration after his summer in southern France and Italy. Circa 1959. Photo: Jane Gate. Courtesy Pangolin London exhibition catalogue.

Missing Mosaics

There are millions of images of Picasso’s work on the internet, yet multiple searches do not produce one single image source for these mosaics. One wonders why? Where are the rest of them? Who bought them? Do they still exist and if so, where are they? One website suggests an estimated 350 of his works have been stolen, more than any other artist. Are the mosaics among those missing assets?

The Williamson book does not indicate the materials used in the mosaics, but legal documents (more on this below) make reference to a fabrication in stone and colored glass (smalti). The pieces were set using the direct method onto wood panel, a common substrate of the era, as shown in the photo above of Boyesen in his studio. Picasso could have painted his design directly onto the wood. One wonders if Picasso himself painted onto the surface or if Hjalmar was transferring Picasso’s smaller sketch onto the board. The mosaic works possess a certain calm, grounded feeling, in no small part due to Boyesen’s choice of setting style. The works are primarily executed using opus tessalatum, a linear setting matrix with the tesserae (pieces) cut to the same general size overall. Round faces, however, called out for a concentric setting pattern, with some directional, curvilinear intervention as needed, seen in the example of Tête Barbue.

“Tête Barbue” (Bearded Head), 37¼ x 28 in, 1958, executed by Hjalmar Boyesen. Sold at auction in 2010.

With their spontaneous simplicity, Picasso’s designs capture a light-hearted quality. The distinct outlines reference his famous “napkin sketches”, though more likely, they were following on the series of 180 drawings of clowns and circus performers known as the Verve Suite and of course his Madoura ceramics, which also used the face as a dominant theme.

“Visage aux mains” (Face with hands), 1956, Ceramic, 42 cm dia. White earthenware clay, Numbered edition of 100. Inscribed “Madoura/Edition Picasso” on verso. Image via: Denis Bloch.

“Visage Etoille” (Star Face), executed by Hjalmar Boyesen, 1957. Perhaps another reference to the parade of “stars” at Cannes in the 1950s. [UPDATE: As a result of the article, this work was identified in the collection of Kunsten – Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Denmark, a museum designed by the world famous Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. The work has been in the collection since 1967. It was included in the 2016 exhibition “Let’s get lost” highlighting Kunsten’s own 20th c. art collection.]

Family Friends

How Boyesen and his artist wife, Dorothy, came to live and work in Cannes during the 50s is unclear, but they were on very friendly terms with Picasso and Jacqueline. [UPDATE: according to my interviews with family, Hjalmar went to Paris to assist with the liberation at the end of the war. He was a lieutenant leading a troop of jeeps, and also a great fan of Picasso. Knowing that Picasso was in Paris, he looked him up. They got on famously and Picasso told Boyesen to look him up: ‘when all this is over, come and find me’. Boyesen duly came back to Europe after the war, and remembering Picasso’s invitation, went to the south of France where Pablo offered him a job. He also met Dorothy at this time and their first two children (of six) were born in Cannes.]

The couples often visited and Picasso celebrated the birth of the Boyesen’s first son in 1958 by sketching Dorothy holding their newborn during a visit to the villa. “I think my husband was so thrilled to have a son that had to be the first thing he did – showing him to Picasso,” said Dorothy in a 2010 news article. “Picasso did his bit to make us feel we had done something extraordinary – as if we’d done something nobody else had ever done.” She added, “I didn’t know he was sketching me until it was time to go.We were saying our goodbyes and he gave me the sketch. I was very excited.”

Mosaicist Hjalmar Boyesen’s wife, Dorothy, holds the sketch made by Picasso after the birth of their first son in Cannes, France. Photo: www.thisisdorset.net, 2010.

Mosaics Held by U.S. Customs

Post-War America was burgeoning with enthusiasm for modern art—abstract works by Pollock, Rothko and deKooning were on the rise—and a lively interaction between Europe and New York was afoot. But the antiquated custom laws were in need of reform if the collectors and museums were to build their collections. Though Picasso’s work had stirred a fair amount of controversy over the years, it was in demand. In this case, it was not the content, but the object itself that piqued debate. When Picasso’s 3 ft. x 2.5 ft. mosaic panel titled Les Joutes was shipped to the USA in 1958, it became the object of a court ruling. U.S. Customs tied up Picasso’s mosaic for over two years, meanwhile identifying it as “bits of glass on stone.” Certain forms of art carried no taxations, while others were heavily taxed due to the “manufacture” of materials used. Mosaic, sculpture, and collage were among the art forms levied at this time.

“Les Joutes” (The Jousters), circa 1957-58, 36″ x 30″, executed by Hjalmar Boyesen. Les joutes nautiques is a boat jousting tournament.

“Picasso was quite annoyed by all this,” stated an attorney representing the petitioner in a N.Y. Times article of May 1959. “He’s annoyed the U. S. Customs Inspectors can be so—shall we say—uncultured”. By September 1959, a unanimous act of Congress amended the Tariff Act of 1930 so the works of art were allowed to enter the country duty free.

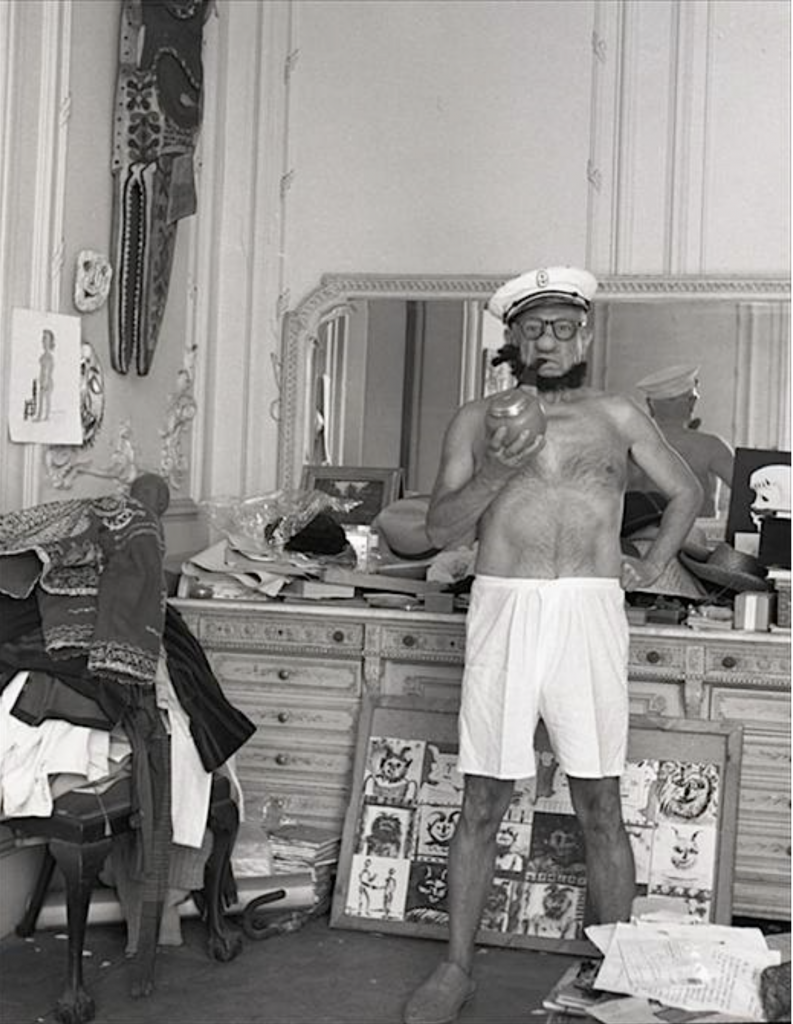

Picasso camps it up as Popeye in his littered Cannes bedroom, standing in front of a bulletin board pinned with “têtes” sketches for ceramics or mosaics. He often worked from bed. Photo: André Villers, 1957. Picasso gave Villers his first Rolleiflex camera in 1953.

End of an Era

The decadent, non-stop party atmosphere of the Cote d’Azur began to take its toll on Picasso’s increasingly private vision. Star-struck journalists were persistent in demanding his time for interviews, while a constant stream of visitors and dinner parties were de rigueur.

Brigitte Bardot visits Pablo Picasso during the 1956 International Film Festival at Cannes. Note the ceramics stacked on the floor and painted tiles in the foreground. Photo: ©Jerome Brierre/Getty Images.

The events that brought mosaic making and Picasso’s relationship with Boyesen to a close are yet to be discovered. We do know that by the late 1950s Jacqueline was fiercely protective, becoming known as a “gatekeeper” amongst his friends. Perhaps in Jacqueline’s attempts to shield Picasso, Boyesen and Dorothy were no longer able to maintain the friendship or working relationship they had once enjoyed? Perhaps the young family departed for England to join Boyesen’s assistant Ralph Brown and the mosaic book author Robert Williamson? [UPDATE: Apparently there was a newspaper article in which Boyesen said something perceived as unflattering which angered Picasso.]

During that decade, Pablo and Jacqueline moved from the villa La Galloise in Valluarius, to La Californie in Cannes, up to the Chateau of Vauvenargues near Aix-en-Provence, where he could work undisturbed. He was quite wealthy by this point, and acquired the magnificent Chateau property in 1958. He moved his vast art collection to the Chateau, which they occupied between 1959 and 1962. Subsequently they moved to Mougins, where Picasso spent the last 12 years of his life. It was in Mougins he died, at age 91, so the story goes, at his own dinner party. Ever the bon vivant, his last words were “Drink to me, drink to my health, you know I can’t drink any more.” It is at the Chateau however, that both Picasso and Roque are buried, and the property remains in the family estate.

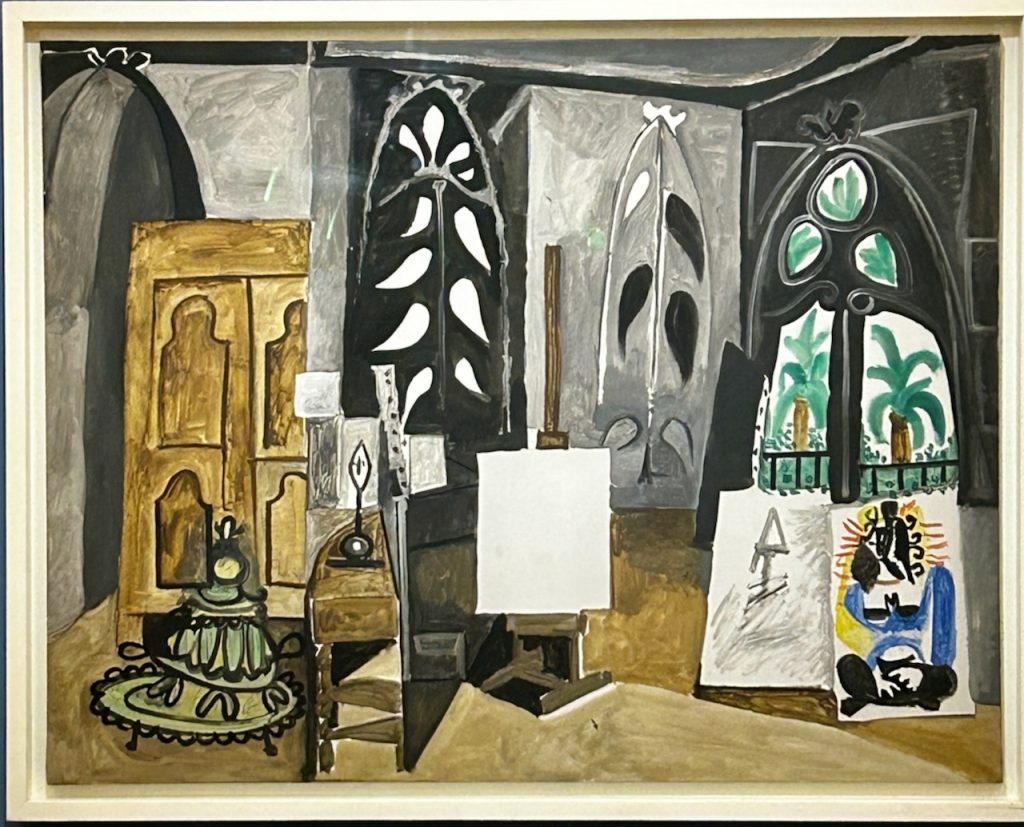

L’atelier de ‘La californie’ a Canne, (the studio at La Californie) 1956, oil, collection of Musée National Picasso-Paris, France. photo by author.

Picasso’s Influence on Mosaics Today

For now, Picasso’s mosaic works seem an enigmatic flicker as it appears art historians have generally passed over this aspect of Picasso’s artistic oeuvre. By publishing this investigation, perhaps further connections to Hjalmar Boyesen’s mosaic collaboration with Picasso will surface. Meanwhile, there is no doubt that Picasso continues to inspire mosaicists today—his paintings, and even his famous face, remain a source for interpretation by artists worldwide.

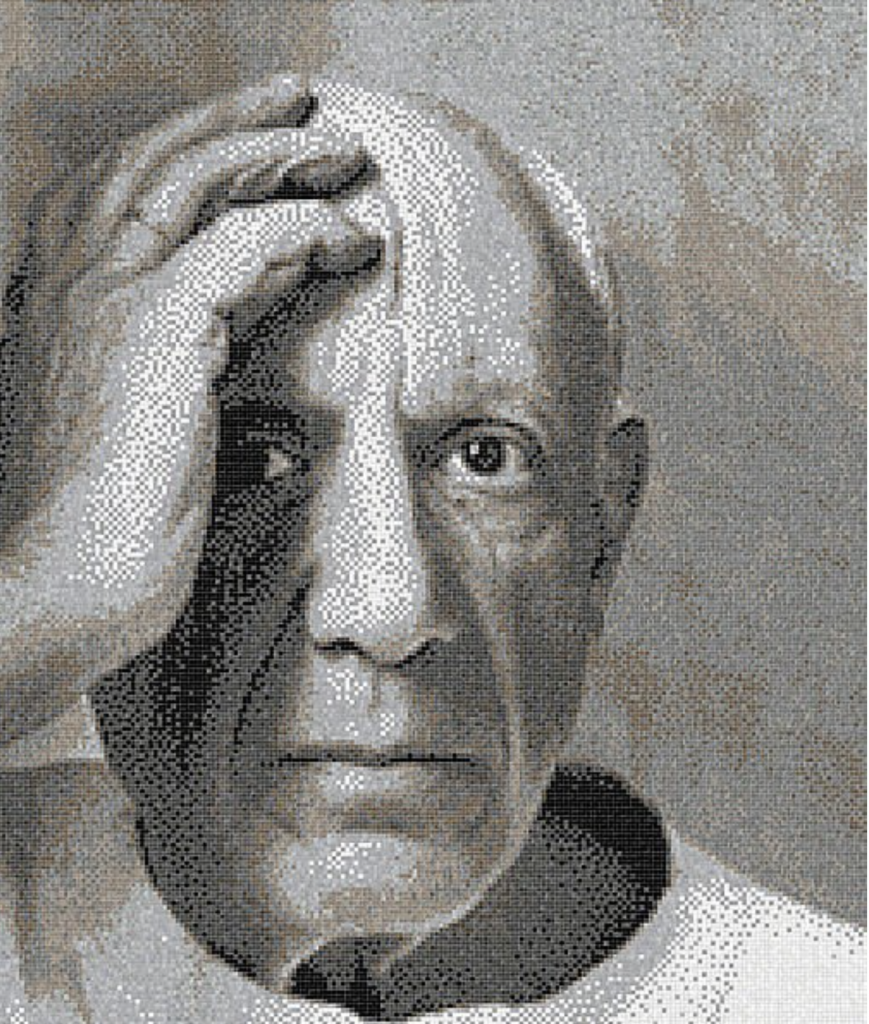

Portrait of Picasso from the Photo Line by Asarota, a French mosaic company.

Giulio Pedrana “Girl Before A Mirror” (after Pablo Picasso) 2012 13 x 105 cm.

Jose Morales “Girl Before A Mirror” (after Pablo Picasso) 2012. Jose is a participant artist in the Piece by Piece Project of Los Angeles, a non-profit mosaic training school where the author is a visiting artist.

A third-year student at the Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli in Spilimbergo, Italy, works on a group project of a full-scale mosaic interpretation of Picasso’s “Guernica”. 2006.

RESOURCES:

UPDATE: Many thanks to the Boyesen family, private collectors, and institutions who have assisted in aiding the update of this story since it was originally published in May 2012. Special thanks to François Dareau, head researcher at the Musée National Picasso-Paris for our years of collaborative communication. He reached out to me in 2018 while researching for a museum project, and we finally got to meet in Fall 2023. He will present on Picasso’s mosaics the UNESCO Symposium in Dec. 2023. The Story continues to unfold…

Williamson, Robert, Mosaics: Design, Construction and Assembly, 1963, Crosby Lockwood, London, Hearthside Press, NY (out of print – but available from used dealers)

“The Day Picasso Sketched Lytchett Matravers Mum”, Juliette Astrup, The Daily Echo, 10 March 2010, accessed 14 May, 2012 http://www.thisisdorset.net/news/tidnews/5050677.The_day_Picasso_sketched_me/

“Ralph Brown at Eighty: Early Decades Revisited”, Pangolin London, 2009, PDF exhibition catalogue.

New York Times, 22 May 1959, p. 18, col. 3 www.nytimes.com

“Congress Rehabilitates Modern Art,” W. Derenberg, D. Baum, N.Y. University of Law, 34 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1228, 1959

Picasso on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pablo_Picasso Accessed 14 May 2012

“Picasso in Vallauris”, Hans Bendix, Harpers, March 1956, page 44.

Françoise Gilot interview in Vogue, June 2012 http://www.vogue.com/magazine/article/life-after-picasso-franoise-gilot/#1

Verve Suite http://www.manhattanrarebooks-art.com/picasso_vervefrench.htm

Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CkRS3wDg1xU Scene from ‘Visit to Picasso’, a documentary by Paul Haesaert . Shows Picasso live painting on glass in his Vallauris atelier, 1949.

Picasso’s ceramics from Madoura Pottery – Denis Bloch Websitehttp://www.denisbloch.com/ceramics_artist.php?cat=Ceramics&name=Pablo_Picasso&medium_id=36&aid=2

“Pablo Picasso’s love affair with women”, Mark Hudson, The Telegraph, 13 Feb 2009 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/4610752/Pablo-Picassos-love-affair-with-women.html, accessed 19 May 2012

“At the Court of Picasso”, John Richardson, Vanity Fair, November 1999 http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/1999/11/picasso-199911 Accessed 19 may 2012

VIDEO: Pablo Picasso Biography – 9 parts on youtube Part 8 addresses the late 50’s, the Velasquez paintings and images of his ceramics. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zXLi9QKaPU4&feature=relmfu

Charlie Rose interview with Françoise Gilot and John Richardson, 17 May 2012 http://www.hulu.com/watch/363070/charlie-rose-picasso-and-francoise-gilot-paris-vallauris-1943-1953

Glass portrait of Picasso, by French mosaic manufacturer Asarota: http://www.asarota.com/

Giulio Pedrana on etsy.

Jose Morales: http://www.PiecebyPiece.org

Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli, http://www.scuolamosaicistifriuli.it Teachers and students of Spilimbergo Mosaic School created the Picasso mosaic. The 8 x 4 meter “Guernica” mosaic is now located at the Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli (Spilimbergo Mosaic School in Friuli)

Please read, comment and like – click to share on any of the social media outlets. Hat Tip and Thanks to MAN editor, Nancie Mills Pipgras for publishing my work.

Where’s Pablo? The Mid-Century Mosaics of Picasso

And what about Picasso Mandalas?? Yes, we have them too. Click HERE